Novels can be a long time in the brewing. Nine years ago, I was on a month-long residency at the splendiferous Centre d’Art i Natura (CAN) in the tiny, high village of Farrera in the Catalan Pyrenees. Take a look at the luscious images and soundscapes on their website to get a sense of the place.1 I knew there was a significant fresco of a medieval woman nearby, near Escaló in the county of Pallars Sobira, and I went to visit it.

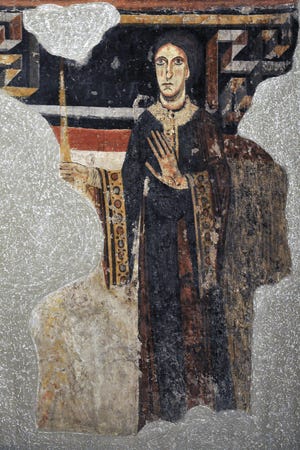

The fresco shows Lucia de la Marca, an 11th-century countess of Pallars Sobira. She was the sister of Almodis de La Marche, countess of Barcelona, who was the heroine of my first novel, Almodis: The Peaceweaver, which had been published a few years before my residency (and is just republished this year).2 Since the fresco of Lucia is lifesize and at floor level, it gives the effect of encountering Lucia herself.

I thought I might write my next novel about Lucia but that idea sat in a drawer (of my mind) for years without fruition, but now she (or her funeral at least) has found her way back into the new novel I am working on.

Setting Out

Lucia was the third daughter of the count of La Marche. The county of La Marche was in the centre of what is now France and roughly maps onto contemporary Creuse. Her eldest sister, Almodis, was countess of Toulouse and then (after being kidnapped), countess of Barcelona. Lucia’s other older sister, Raingarde, was countess of Carcassonne. Lucia’s marriage was arranged by her powerful sibling, Almodis, and I imagine her as a young woman at the court in Barcelona from 1053 or 1054. On 11 December 1054, Lucia was betrothed to Guillem II, count of Besalu and Ripoli, as part of an alliance between Besalu and Barcelona. Several commentators of the time described Guillem as angry, violent and irascible. His nickname was Trunnus, because he wore a false nose, having presumably lost his own in battle.

Luckily for Lucia, Guillem changed his allegiance, jilted her and married someone else. Almodis and Ramon then negotiated another marriage for Lucia to the ageing count of Pallars Sobira, Artaldo I. The couple were married early in 1057 and Lucia was soon producing heirs. When her husband died in 1081, her oldest son was still a minor, so she ruled as regent for 10 years. She was also appointed tutor of another minor, Count Ermengol IV of Urgell, making her a powerful force in the region.3

This fresco painting of a medieval countess is highly unusual.4 It provides the only real clue to what the two sisters might have looked like. There are a few other illustrations of Almodis, but they are in a generic medieval style and give little away. I’ve always liked to imagine Lucia herself commissioning the fresco, but its dating and the fact that she is holding a lighted candle indicate that it was created soon after her death and commissioned by her sons, Count Artaldo II and Bishop Ot d’Urgell. Nevertheless, perhaps she had planned the commission with the artist, including its unusual scale and position and her sons simply saw the plan through. At the top of the wall was Christ in Majesty, but only his foot has survived. Beneath him is a band with the Virgin Mary and five apostles, and below them and to right of where the altar would have been, was Lucia. A white inscription identifies her by name. Her image is eye-level with the viewer and would have been eye-level and ‘accompanying’ the priest as he celebrated Mass.

The Master of Pedret

The paintings at Sant Pere del Burgal were created by the Master of Pedret who worked in the region from about 1080 to 1120. The artist probably travelled as part of a team executing commissions. His distinctive style is seen in the borders of geometric motifs and his ziggy angels at Santa Maria d’Àneu. These seraphims have no less than three pairs of wings each, which are studded with eyes. The style has its roots in the Byzantine Empire, by way of Italy, to Catalonia. Possibly, the Master of Pedret was Italian.

Tug-of-War

The Benedictine monastery of Sant Pere del Burgal was founded before the 9th century.5 Before the monastery was built, monks lived in caves in the mountainside. The monastery became the subject of a dispute between the Languedoc abbey of Lagrasse and the Catalan abbey of Gerri. Sant Pere del Burgal is mentioned in a charter from Raymond I, Count of Toulouse in 859. Surviving in the remote Pyrenees would have been a struggle, and early in the 10th century, in 908, there were only two monks left. They transferred themselves and Sant Pere to the large Catalan abbey of Gerri and the patronage of Count Ramon II of Pallars-Ribagorca. When the count died, however, he donated it back to Lagrasse Abbey in Languedoc, perhaps already an indication of the dispute. In 948, an Abbess Ermengarda bought it back for Gerri from Lagrasse. False documents were generated at Gerri to try to secure ownership. In 1006, Count Sunyer of Pallars confirmed it to Lagrasse again. The church was built in the second half of the 11th century, presumably commissioned by Countess Lucia de la Marca. In 1337, Sant Pere was confirmed to Lagrasse again, but then it was returned to Gerri in 1770. I have to wonder, what was worth this nine-centuries’-long haggle? The nearby river is forceful and may have generated wealth. Gerri had its own salt mine and perhaps Sant Pere del Burgal was also sitting on such a natural resource. More research beckons!

On the Back of a Mule

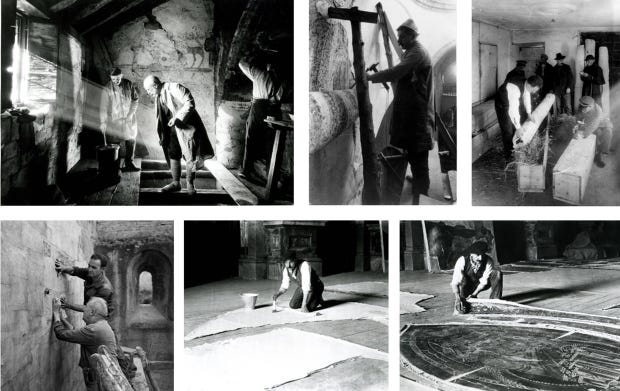

In the twentieth century, the string of remote chapels in the Pyrenees were threatened with vandalism, theft and damage from natural causes and neglect. In 1924, the fresco including Lucia was removed by Italian restorer Arturo Cividini and mounted on separate flat panels using the strappo technique. Cotton cloths impregnated with gelatin were placed over the painted surface. When the glue dries it is strong enough to detach a fine film of the paint, which sticks to the cloth. The cloth was rolled up and transported from the Pyrenees to Barcelona on the backs of mules. I imagine Lucia’s image making that journey. Very good replicas were left behind in the mountain chapel.

The paintings were acquired by the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC) in 1932. MNAC has one of the largest collections of Romanesque wall paintings. Chemical testing showed that the paint layer is composed of yellow (goethite), red (haematites) and black (carbon). White brushstrokes were applied as the final decoration. Green and grey were mixed from the main colours. Aerinite was usually the blue used in Catalan Romanesque painting. The pigment was obtained in the Pyrenees and was therefore cheap. In Sant Pere, however,

we see another kind of blue: the azurite used to colour the keys that Saint Peter is holding in his hand. This blue is a pigment that was also used in ancient times. However, it was not found so locally and was therefore more expensive. .. The artist used it to create an important symbolic feature, the keys to the kingdom of heaven.6

A mixture of lime, grated cheese and milk was used to transfer the paintings to new canvas supports. The conservation department tested for microbiological growth on the paintings and decided on their optimum conditions: around 22 degrees c during the hottest months and 20 degrees c during the coldest, with an annual humidity of 58%.

In 1973, the splendid architectural installation in the form of an apse, mimicking the chapel, was created in MNAC, where Lucia (or her image) can now be visited. In 1964, another fragment from Sant Pere was removed by Ramon Gudiol and was restored at MNAC in 2015.7

Circling Back

Lucia travelled from Charroux in La Marche, central France to Barcelona, probably via Carcassonne and Narbonne, and then to Pallars Sobira. And then her image undertook the return journey back to Barcelona.

Talking to friends in the village of Farrera recently, I was sad to learn that ‘the last shepherd’ has just hung up his crook after his flock was attacked by a bear. The sound of the sheep bells along the mountain tracks above the village was a constant melody during my residency. The pros and cons of rewilding the Pyrenees with wolves and bears was under discussion when I was there nine years ago.

Farrera has become the birthplace of my new heroine in the novel I am writing, the female troubadour, Beatriz de Farrera. I am sending a wave to the retiring director of CAN, Lluis Llobet. Immense thanks for the continuing inspiration you and CAN gave me. And by the way, I’ve given your name to a sculptor in my novel, the (fictional) son of the Master of Pedret. He is the ‘love interest’ in the novel too.

Centre d’Art i Natura de Farrera https://farreracan.cat

Warr, T. (2023) Almodis: The Peaceweaver, Meanda Books. https://meandabooks.com

Cawley, Charles (2022) Medieval Lands: A Prosopography of Medieval European Noble and Royal Families https://fmg.ac/Projects/MedLands/ANGOULEME.htm#AlmodislaMarchediedbefore1078

Silke Engelhardt, ‘The Apse of Sant Pere de Burgal - Female Agency in the Image’, Ruprecht-Karls-Universitat, Heidelberg. https://iberome.hypotheses.org/files/2022/08/Iberome.Engelhardt.07.09.2022_English-1.pdf

Monestir de Sant Pere del Burgal http://www.monestirs.cat/monst/pasob/ps08pere.htm

Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, ‘A group of Apostles out of place: Mural Paintings from Sant Pere del Burgal / 2’, Blog del Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 12 Nov 2015

Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, ‘The Mural Painting Transfer Kitchen’, Blog del Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 12 Mar 2015 https://blog.museunacional.cat/en/mural-painting-transfer-kitchen/

Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, ‘A group of Apostles out of place: Mural Paintings from Sant Pere del Burgal / 1’, Blog del Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 29 Oct 2015