Since a purloined and partially destroyed letter is an important clue in the medieval murder mystery I am writing, I needed to get my facts straight about the materials and processes used for writing medieval letters.

It is likely that the letter in my novel was written in Latin and dictated to a secretary, rather than directly written by the sender.

This self-portrait of Hugo Pictor shows the tools of the scribe: a sloped desk, inkhorn, quill, penknife (for scraping off errors). A compass or dividers were used to score or prick a precise grid of lines onto the blank page to keep the script straight and to make the margins and columns consistent. Manuscripts were held open with weights on strings during copying.

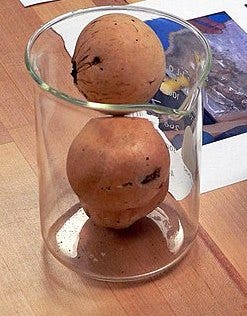

The writing surface was usually parchment made from scraped animal skins. The scribes often had to work around holes and other flaws in the parchment. Parchment was oblong in shape, because cow, sheep and goat skins are oblongish. The quill was usually made from a goose feather and had to be carefully trimmed to allow a good dispersal of ink. The inkhorn was made from cow horn. The ink was usually iron-gall ink, which was made from oak galls, ferrous sulphate and gum arabica (from accacia trees). It was purple black or brown black and indelible. Galls are small, pale green or brown, apple-like balls on plants and trees, which form around wasp eggs.

Iron-gall ink is acidic and bites into the parchment. Even if it fades or is obliterated, it leaves a trace burnt into the surface that can be deciphered. Earwax and urine are other ingredients that have been detected in some medieval inks.

The coloured pigments used in illustrated manuscripts were extremely expensive, as were the parchment leaves and the decorated book covers. And then there was the time it took scribes to create a handwritten manuscript. In early 11th century Catalonia, a small book was worth two horses. Charlemagne had luxury books written in gold or silver on purple-stained parchment.

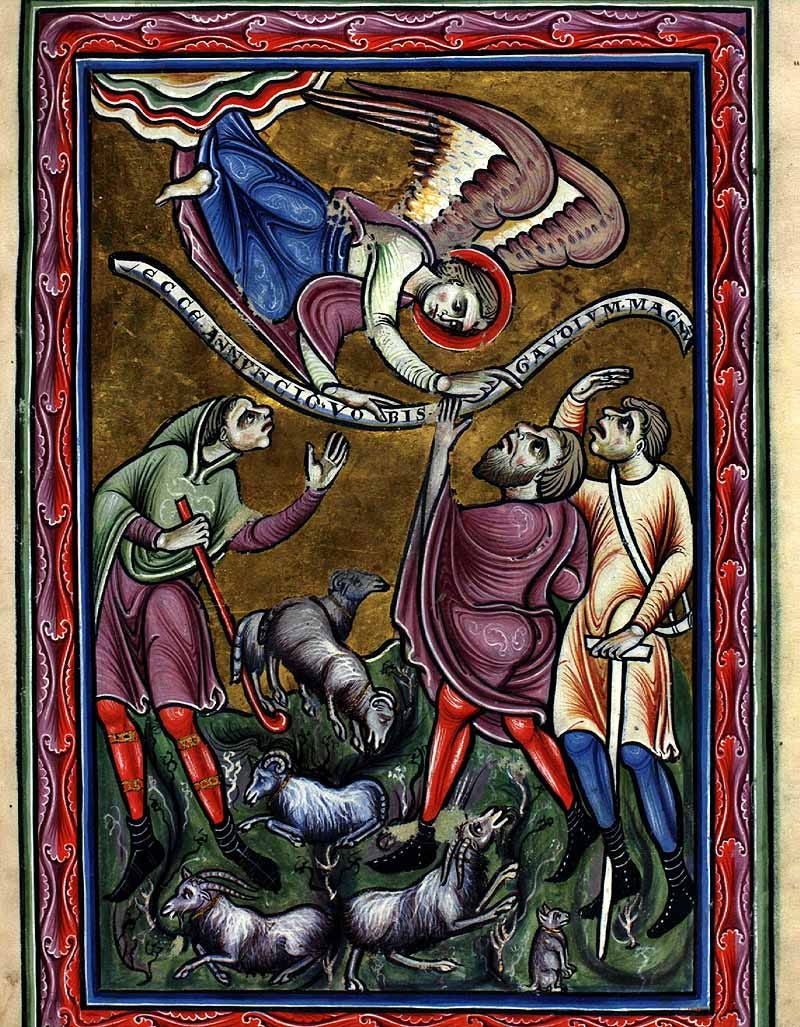

The 12th century Copenhagen Psalter, which was made in England, had real jewels glued onto one page. It had tiny sewing holes above or beside every image and every illuminated initial, which shows that they were once concealed behind little textile curtains that were stitched onto the page.

At the monastery of Cluny, the monks were allowed one book to read per year and there was an annual book changing event. A good choice to get you through the year, might have been the enormous Codex Amiatinus, which was created at Wearmouth-Jarrow Monastery. Although, falling asleep reading would have been a serious problem.

The 8th century Codex Amiatinus has 1,030 leaves made from 515 sheep and goat skins and weighs in at 34kg – about the same as a 12-year-old boy.

The medieval manuscripts that have survived into the 21st century have run the gauntlet of fire, flood, war, revolution, rodents, Vikings and Nazis. Vikings often stole books and ransomed them back. The 15th century Duc de Berry’s Tres Riches Heures and the 14th century Jeanne de Navarre’s Book of Hours were among Nazi loot – stolen from Rothschild family members’ bank vaults in Paris.

Medieval books were also at the mercy of their readers. A number of manuscripts have the faces of the Antichrist and the Whore of Babylon, for example, scratched out by irate readers. More recently, medieval manuscripts have suffered from having pages cut out and sold on the black market, or from scholars who purloined individual pages for their own collections and framed and hung them in their own houses. For more on medieval manuscripts and the extraordinary stories surrounding them, I highly recommend Christopher de Hamel’s lively book Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts (London: Penguin, 2018).

Other Sources of Information

Doyle, K. & Denoel, C. (2018) Medieval Illumination. London: British Library.

Epistolae: Medieval Women’s Latin Letters at https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu

Hollander, H. (1974) Early Medieval Art, trans. C. Hillier. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

A Selection of Digitised Medieval Manuscripts to Explore

Bibliotheque National de France https://www.bnf.fr/en/gallica-bnf-digital-library

Book of Kells https://digitalcollections.tcd.ie/collections/ks65hc20t

British Library https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/

Carmina Burana https://www.wdl.org/en/item/14698/

Copenhagen Psalter http://www5.kb.dk/permalink/2006/manus/242/eng/

Digital Bodleian https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk

National Library of Wales https://www.library.wales/discover/digital-gallery/manuscripts

So interesting to read about how they used parchment and made ink. We take books for granted now and many don’t use them at all… substituted with phones and kindles. Personally I love wandering around a book shop. Being an artist myself, I found the ink making really fascinating. I won’t be disturbing the wasps though!